It is easy to quickly recognize the beauty of the Mamoni landscape. Multiple hill tops spread across the landscape were visible from the road to Mamoni Arriba. The surprise I felt laid in the fact that these hills and mountains were fully covered with jungle and not cattle pastures. These days, mountain tops covered with jungle are rare sights in the Panamanian country side, but not in Mamoni. I felt proud and content to be part of this journey into the Mamoni Valley.

I parted from Panamá city early in the morning towards the North East into Mamoni Arriba. My objective was to meet the local people and understand the landscape so that I could plan a longer visit. Luckily for me, I was accompanied by Roland who was born in Mamoni and has been working for Earth Train for many years. I was also accompanied by Carlos Andrés who is a Panamanian lawyer that works for Earth Train and has spent valuable time working in the valley. I had been warned about the access road to Mamoni Arriba because during the rainy season it becomes difficult to ride. However, Rolando’s driving skills did the trick and got us to Mamoni Arriba in no time.

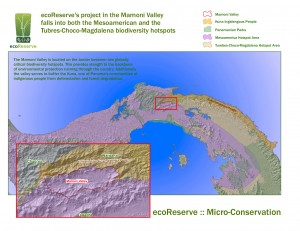

The landscape going down the road and into the Mamoni valley was truly amazing. The valley per say was mostly covered by pasture land. In the background I could see the mountains that surround the valley and that are shared with the Chagres National Park and the Comarca of Kuna Yala. The forest that lies on these mountains is what we in ecoReserve are working to protect. I was imagining myself crossing the mountains to Kuna Yala when Rolando decided to stop at “el filo”. El “filo” is the spot with the highest altitude on the road to Mamoni Arriba. Rolando showed me the Caribbean towards the North. I knew it was the Caribbean because I could clearly see the islands that are part of Kuna Yala. I’ve never visited these islands but now I can say that I’ve seen them from a distance.

Once we made it to Mamoni Arriba we met with Arsenio. Arsenio is a very funny man and with a lot of energy. I wanted him to take me to the forest, to a very “specific spot”! Since I had never been in the valley the only way I could explain to him where I wanted to go was by showing him an aerial photography of Mamoni Arriba. In somewhat of a silly manner he told me that, “he couldn’t understand the image because the highest altitude he had ever seen his house from was 14 meters”. I immediately thought to myself how I had felt the same way the first time I looked for my house on Google earth. I started laughing.

We spend quite sometime figuring out a way to reach the “specific spot” that I wanted to visit. We figured out our starting point for my next visit. The starting point will be where the Espavé stream connects with the Mamoní River. I met with many more people and got a very good feeling for the site.